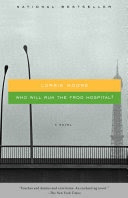

Welcome to the Frog Hospital

Lorrie Moore (1994)

Lorrie Moore was wandering through an art gallery when she came upon a painting called “Who Will Run the Frog Hospital?” The work, by Nancy Mladenoff, depicts two young girls regarding a pair of bandaged frogs. Ms. Moore not only bought the painting, she also borrowed its title and imagery for her second novel.

The novel is narrated by Berie Carr. While vacationing in Paris with her husband, Berie recognizes that her marriage is deteriorating, noting that “I feel his lack of love for me. But we are managing.” Facing this disappointing state of adulthood, the book narrates her recollections of an adolescence in Horsehearts, New York. Berie looks back to 1972, when she was a wild teenager with her best friend Sils. They had summer jobs at Storyland, an amusement park where Sils plays the part of Cinderella and Beris works as a ticket seller. The emotional heart of this short novel is the intense friendship between the two young women. Berie is nostalgic

for that summer in which she felt so alive: smoking and drinking and sneaking out, the passionate connections, the fearless quality that is so yearningly absent in her life as she approaches forty with a philandering husband and no zest for the present.

Moore’s precise period details take us to a specific moment in American history: the music, the styles, even the lip gloss, are familiar to readers who grew up in that time. As is the political climate, the illegality of abortion in much of the country, the gendered assumptions.

In our discussion, we differed widely in our response to the book. I was perhaps the most negative, confessing my disappointment in reading such a negative, hopeless account of a narrator less than half my age who yearns with such nostalgia for a lost adolescent exuberance and girlhood friendship but who, at not even forty, in good health, has so much time left, so much she can do, can choose. I wanted her to get a life in the present, to develop underdeveloped aspects of herself.

Other members of the group enlarged my appreciation of the novel, describing it as sad, and quite accurate to how it can feel in middle life, to be stuck, not in the adult life one imagined, and yearning for a romanticized intense lost youth. One reader commented that if the marriage is hopeless, Berie may leave it and that she probably has decades of new experiences ahead of her. Another reader read us the narrator’s description of singing in a girls’ choir and noted the magic and hope contained in that uplifting passage. Some readers and reviewers enjoyed tagging along with a narrator through memories of a youth so much more wild than their own, particularly when we are not troubled by the fear she will not survive it.

It occurs to me that we really reacted to Berie as a person, or a cipher for the author, rather than a character designed by Moore to show us a set of emotions and memories. And that response speaks to Moore’s success as a writer. I will end with a couple of examples of her precise and powerful prose:

On her husband:

[H]e studied Spanish once, and now, with a sad robustness, speaks of our childlessness to the couple next to us. “But,” he adds, thinking fondly of our cat, “we do have a large gato at home.” “Gâteau means ‘cake,'” I whisper. “You’ve just told them we have a large cake at home.” I don’t know why he always strikes up conversations with the people next to us. But he strikes them up, thinking it friendly and polite rather than oafish and irritating, which is what I think.

On femininity:

I remember thinking that once there had been a time when women died of brain fevers caught from the prick of their hat pins, and that still, after all this time, it was hard being a girl, lugging around these bodies that were never right – wounds that needed fixing, heads that needed hats, corrections, corrections.”

After listening to our animated discussion about the plot, the character, and the writing, a reader who had lost interest in the novel and set it aside decided to finish reading it.