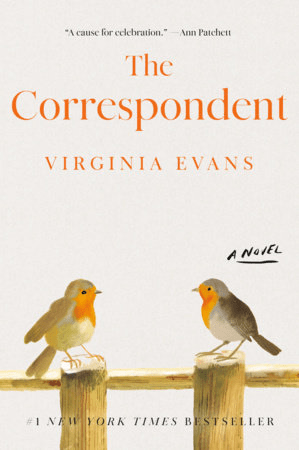

Virginia Evans (2025)

This debut epistolary novel reminds us how important letters are.

Sybil Stone Van Antwerp lives alone in retirement from an impressive career in law. Kind and reserved, she misses the clarity and order of the law.

Her life is not empty, and yet she is alone, tending to her garden, and involved with a variety of family members, local organizations, and old friends through her meticulous letter writing practice.

We learn that she fell apart after the death of her son Gilbert, age 8, in a diving accident while in her care. She was focused on a legal document from work and not paying attention when he dived into the river and broke his neck on its rocky bottom. Her marriage to Dan could not survive; both grieve, and he returned to his homeland, Brussels, taking their two younger children, 4 year old Fiona and 1 year old Bruce with him.

The novel gradually reveals the long term effects of Gilbert’s death.

She buried herself in her work while still reeling with grief and made a fatal judgement in her legal role, one driven by her rage and sorrow which causes great harm.

We all agreed that we are glad we read this novel. We had not known when we chose the novels or their order that, as in our previous book Hamnet, this novel dives deep into the narration of a grief stricken mother after the death of her son.

We talked about the competing pull of profession and family life, and how carefully and subtly the novel captures Sybil’s sense, as an adoptee, of being on the outside, even as her adoptive family is wonderful. In one plot strand, she navigates the gift of a DNA test, and we talked about modern ways of tracing one’s identity by sending off a saliva sample.

We enjoyed Sybil’s eventual discovery of a sister and extended family in Scotland, her tender friendship with widowed neighbor Theordore, and the realism of the break with Rosalie and then the renewal of their friendship.

We really appreciated the ways in which Sybill’s letters were so different in tone, tailored toward each of the recipients with precision and care. She can be formal and curt in one letter and delightful and encouraging in another. Her warm connection with her fellow adoptee, her brother, her careful intelligent writing to Joan Didion, her insistent refusals of garden club and university decisions she deems unwise or unfair, and her humane interactions with corporate workers, all build a real sense of a fully developed complex character.

We did wonder why the author included the loud flirtatious retired lawyer from Houston, speculated that he made her laugh and perhaps helped to open her up to friendship with Theodore, as well as showing us that she is of romantic interest not just to Theodore, and we appreciated this vision of possibility and flirtation in later life.

Her relationship with a colleague’s young son Harry is a particularly compelling epistolary connection, as we see her deep care, her mothering of this young troubled boy with respect and real interest in his individuality, and so glimpse a version of her that her adult children do not see.

Her impending blindness is what initially drew me into the book, and then I was so caught up in her web of characters and the other plot points that I lost track of that until near the end. Her vision seemed to deteriorate much more rapidly than my own, but her loss of independence and need to rely on others for driving and for companionship in travel rang true.

We appreciated the ways in which the novel is redemptive without veering into fairytale happily ever after. I appreciated the novel’s quick, silent death, alone at her writing desk, and the ways in which her unsent letters are discovered and help her family and close friends to understand why she did not attend Dan’s funeral and to grasp the extent of the devastation and intensity of her loss of Gilbert.