Want to read with us? Our Fall Schedule

A little background: Our book group’s origin was my final course before full retirement from Mills College in the Spring of 2020; it was a wonderful collaboration between a Mills English course “Coming to Age” and the Downtown Oakland Senior Center, in which students and seniors met together. The pandemic cut short our in-person discussions, and we turned to Zoom. After the semester ended, members of the senior center proposed we continue on Zoom on our own.

At first, I continued to select the books and was responsible for coming up with discussion prompts, but over time our process changed in wonderful ways. For example, at each meeting now, every member shows up prepared to call our attention to a particular passage or to consider a question or theme. We never know in advance where our discussions will lead, and it is wonderful to note the similarities and differences between what captures our attention and how we have responded to the passages, and texts, we have chosen.

We meet in sessions that generally run about eight meetings (or four per month). We meet twice a month over the session, and we all participate in selecting books. Before the end of each session, we all submit titles and brief descriptions of two or three books we have read and recommend. Two members, Patricia and Carole, helpfully type up the list and send a group email. Then, at the session’s final meeting, we vote to select eight books for the next.

We focus primarily on fiction (novels or short story collections)by women that feature an old woman as protagonist. Occasionally, we select fiction by a man or we digress from fiction to a collection of essays. However, over the five years we have been meeting, most of our selections fall into our original category: fiction by women with older women protagonists.

If you’d like to read along, our fall/winter session is August 11-November 24.

August 11: Mrs. Quinn’s Rise to Fame by Olivia Ford. 2024; 384 pages.

August 25: Three Things About Elsie by Joanna Cannon.

2018; 372 pages.

September 8: Erotic Stories of Punjabi Widows by Balli Kaur Jaswal. 2017; 304 pages.

September 22: The Snow Child by Eowyn Ivey. 2012; 389 pages.

October 13: Cat Brushing and Other Stories by Jane Campbell; 2022. 245 pages.

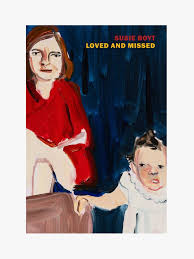

October 27: Loved and Missed by Susie Boyt; 2021. 208 pages.

November 10: An Unnecessary Woman by Rabith Almeddine; 2012; 291 pages.

November 24: Stone Yard Devotional by Charlotte Wood. 2024; 320 pages.