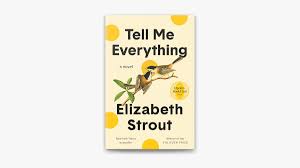

Tell Me Everything (2024) by Elizabeth Strout

“A generous, compassionate novel about the human need for connection, understanding and love, and the damage that occurs when those things are denied.”—San Francisco Chronicle

Elizabeth Strout returns to the town of Crosby, Maine, and to her beloved cast of characters — Lucy Barton, Olive Kitteridge, Bob Burgess, and others. In this novel, the community must navigate a shocking crime in their midst.

Our book group previously had read Strout’s Olive Kitteridge at my suggestion. I had taught the book at Mills, and the students found the stories engaging and thought provoking. The book group agreed, and we eagerly returned to Strout’s characters in Olive, Again, Oh, William, and Lucy by the Sea, so when we saw the announcement of Tell Me Everything, we immediately added it to our fall 2024 reading list. We anticipated Strout’s familiar conversational style, her quirky characters, with a central plot threading together all the bits and pieces. dWe were surprised by the larger cast of characters, the multiple plot lines, and we were a little disappointed.

We had not been put off by large casts of characters or multiple plot lines in other books, and we wondered why this book, well reviewed as the Chronicle quote above indicates, did not sit well with us.

Perhaps we expected her more familiar form. Unlike novelists whose books do not return to the same places or characters, Strout’s connected novels, while not formally a series, create a fictional world that invites readers to return to a place they know well, offering new surprises and plots but within an expected structure. So the shift in structure, as it did not have a clear point–was not obviously making an argument via form–put us off a bit.

We also had feelings about the characters’ fates. We have leaned into novels with tragic or or unhappy outcomes, but here we were invested in the characters across a series of stories, and so our reactions and expectations differed. Perhaps we were perplexed by the choice to make Lucy remarry William, whom none of us really like. One group member wondered why she built up the intimacy between Lucy and her friend Bob Burgess only to alter it so abruptly. We speculated that Lucy married William to force herself to loosen the ties to Bob. Our reaction, as if these are people we know, is fascinating to consider. For example, long after my initial reading and weeks after the group discussion, I still feel the initial burst of satisfaction I had when Olive’s good friend in the memory care section of their shared nursing home defied her daughter’s insistence to move across the country near family and insisted she needed/wanted to stay close to her best friend, Olive.

Strout’s characters always feel “real,” and her writing is always strong, but I wonder about the dangers of writing a series of linked novels, as well as the pleasures. I did not, finally, enjoy this novel nearly as much as the previous ones. I’d love to know what you think!