It has been a very plot-driven end to the year 2025 at every level, local, national, international. Like the protagonist of Charlotte Wood’s 2023 novel, we have all been buffeted by the cruelty of what Wood calls, “the broken world,” even as we have cheered on individuals and communities who insist on resistance and hope.

In the midst of the chaos, my husband and I both had medical emergencies (we are mending and home now), and I was grateful for our group, both because the picked up the pieces and kept things going (including taking the leads for two books in discussions and the blogs I am finally posting, and for the continuity and community of our shared reading and conversation experience, more needed than ever.

Health issues are present at any age, but certainly shape the reality of aging for most of us, and to be supported with medical care, and a strong community is a gift I wish for all of us in this, and every, stage of life. I am delighted to share group member’s smart comments on the final books of our last season.

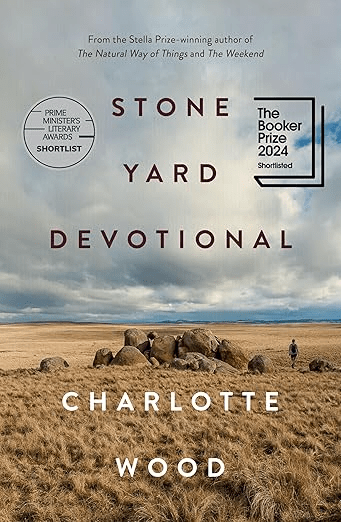

Stone Yard Devotional by Charlotte Wood

Crushed by the seeming hopelessness of the broken world, the narrator of this novel, who works in species conservation, despairs at the ways we are destroying the planet, one another, and ourselves.

She leaves her life in Sydney, including her marriage, iand checks into the retreat house of an enclosed convent on the Monaro Plains in New South Wales.

As the Guardian reviewer notes,

“retreat she certainly does. For a while she just lies on the floor.”

Eventually, she participates in the life of the convent – joining the other women doing daily tasks of preparing food, cleaning, turning up to mass and the hours of office. There’s no epiphany, no conversion narrative, just a quiet story of people tending to things.

Liz L. writes:

I enjoyed this book. It felt very meditative and stream of consciousness but had enough character development and emotional content to keep me interested and reading.

I was fascinated that the narrator was unnamed. I didn’t even realize it until I was thinking about the book for group discussion! I loved the relationships that the narrator had with the other women in the retreat center and with Sister Helen Parry and with her mother. I loved the stream of thoughts and remembrances and ideas that seemed to flow from the narrator in a constant river. It felt very real and real life – like something I do at times when I remember the past.

From Patricia:

In an interview for the Booker Prize, Charlotte Wood, the author of Stone Yard Devotional,said,

“I wanted to master what Saul Bellow called ‘stillness in the midst of chaos.’

I think Wood accomplished this masterfully. The major voice in this novel is an unnamed woman. We learn that she has left job as a manager in an environmental non-profit. The narrator very briefly also mentions a husband she is leaving, but the novel is not larded with the details of her adult life before she visits the abbey on the Monaro plains in New South Wales. After a few short visits to the abbey, she returns and simply stays. We follow her as she shares the life of this community

of cloistered sisters. The silence and simplicity of her life in the abbey allow her to examine memories of her childhood. As she, with the other sisters, confronts a plague of mice and the tensions surrounding the burial of Sister Jenny, a nun who left the abbey for missionary work in Thailand, the narrator slowly finds a measure of peace with herself.

Annette writes:

Like others in our group, I read this novel in several sessions because there was no plot to carry me forward. Shortly before our Zoom meeting I realized I had had about ¼ in of pages left to read, right where the unnamed narrator and Helen Parry, the activist nun, drive around together stopping for a moment at various places where significant things happened in their youth.

My inability to sense where the novel was going relates to something the author said, as reported in LitHub. “There’s a lot of teaching and admonishing and explaining that goes on in contemporary fiction and I was sick of it… I have this setting of silence and stasis which is not good for a novel… I’m kind of writing a still life painting.” Her friend Jude Rae, a painter of still-lifes, gave her advice for achieving an appealing movement.

Toward the end it seems that the narrator and Helen express their feelings about their mothers. The narrator has become more aware and respectful of her mother’s activities to better the world and also sees them a failure. Both the narrator and her mother tried to do good (through environmentalism and helping refugees, among other things) but they tended at times to distance themselves from addressing local troubles. The narrator’s mother had never visited Helen’s mother. The narrator had joined in cruelty to Helen at school, and in adulthood chose to imagine that the man by the side of the road who disappeared down a covered drain was a worker and everything was ok.

In interviews, Charlotte Wood talks about bush fires, COVID, the mouse plague and floods—all evidence of imbalance. As a middle-class white woman who wants a moral way to proceed in the world, perhaps she lays out some considerations in this novel.

Local vs worldwide activism; kindness vs effective disruption (privileged generosity vs dangerous activity); responsibility vs despair; direct activism vs talking/convincing others; and exploration of retreating into silence and routine to confront oneself, to do the least harm, or to do nothing.

The stark setting in New South Wales, beautiful to some and terrifying to others, was described in a visual way (like a still-life?) that provokes emotion and thought: the old cemetery with trees and the newer part a lawn with orderly identical headstones and faded plastic flowers here and there; the boulders in the larger landscape; the weather in which scenes in the novel take place.

Local place names in such variety would provide orientation to inhabitants of a nearly undifferentiated expanse; but in this novel they seem enigmatic, part of the mood.